GitHub and Git; Intro to Sound unit

Texts to have read/watched:

- Git and GitHub for Poets, starting at least with the Introduction

Work to have achieved:

- Download and install what you need to use Git: at the command line and, optionally, using the Desktop app

Plan for the day

- GitHub for Poets review (25 min)

- First project: Soundscape Narrative (20 min)

- What Git does better than GitHub (5 min)

- Multiple views of the same files

- A little command line setup for Soundscape Narrative

- HW Preview

1. GitHub for Poets review (25 min)

EXT: What do you think are the limitations of the GitHub interface? What are some things you might want to do with Git that you haven’t yet seen? Conversely, what do you think GitHub, as a website, might do better than Git?

Okay, so back to full-class discussion. What stands out?

2. First project: Soundscape Narrative (20 min)

As I explained in the syllabus, your first project is to arrange layers of sound to convey a sense of place and story. In assigning this, I have two main goals for you:

- to learn how to capture sound and edit it using digital tools, and

- to explore the affordances of sound as a medium,

with particular attention to its ability to communicate

- immersive environment and

- narrative pacing and change.

Let’s read through this together.

3a. What Git does better than GitHub

As you’ll have learned from the videos, GitHub is a (mostly web-based) file-sharing and project-management platform built on top of Git – the version control system that runs mostly on text commands. GitHub’s pretty, well, pretty.

Super-technical people may have many more reasons than I want to get into. For today, let's focus on a few quick victories...

- Git lets us "stage" multiple files at once and wrap them in a single commit.

- Git lets us keep track of small changes locally before we're ready to share them with the world – and then to "push" multiple commits all at once.

- Using the command line lets us access and activate more features of Git than the GitHub defaults allow.

All of that depends on getting your files from GitHub onto your own computer, while still keeping them linked and tracked.

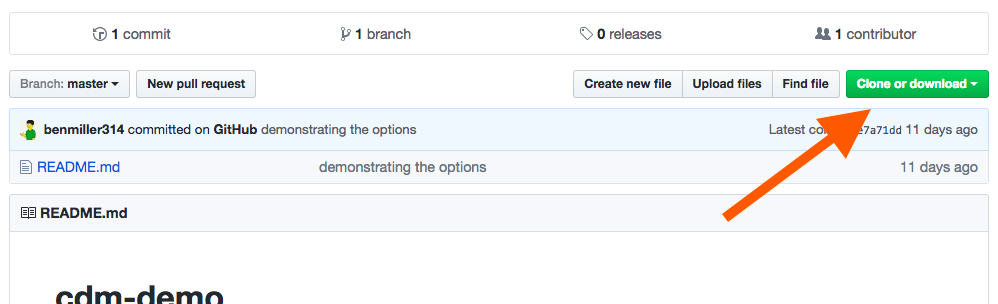

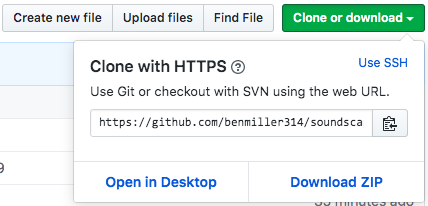

Which means it’s now time to clone the repository you just created: that is, let’s download it and make sure we’re still tracking it with the same Git commit history.

There are three ways…

- download zip

- command line:

git clone %clone_url% - open in desktop

4. Multiple Views of the Same Files

Where do the files go when you clone them? You could use Windows Explorer or Mac Finder to open the folder…

… but how to do commits there? How to see file history?

Enter the command line, a.k.a. Terminal on Mac, or GitBash (or PowerShell) on Windows.

Much as a repository is just another name for a file folder you’re tracking, the command line is just another way of seeing the files you’re used to seeing in windows. (Lowercase ‘w.’)

Moving around at the command line

To get where you’re going:

cd path/to/your/folder # change directory

pwd # print working directory (i.e. where am I?)

ls # list directory contents

cd .. # go up one directory level

cd ~ # go to home folder

To clone a remote repository (i.e. a project on GitHub): grab the URL from that download button and use it instead of the %remote_url% in this command:

git clone %remote_url%

(Note that you’ll then need to cd into the directory that creates.)

To see what git is tracking:

git status

Basic git workflow:

git status

git pull # download changes from GitHub

git status # start of loop

# here you make changes to your files

git add %filename% # optionally repeat

git status

git commit -m "your headline commit message - note the quotes" -m "your optional extra details, if you want them, just go in a second message."

# repeat loop as desired

git push # publish your changes

Yet another view

Alternately, if you’ve downloaded https://desktop.github.com, you can use a visual interface to accomplish all of those local commands. And it’ll also generously prompt you to push changes when you’ve finished committing them.

(NB: If you haven’t tried GH Desktop in a few years, it’s vastly improved since then.)

3b. Back to making use of Git outside of GitHub

- rename the README.md file to ASSIGNMENT.md, and

- create a new README.md file that describes, in your own words, what you think you might make in this space. (Don't worry, you can always change it later.)

EXT: If you’re already good with all this – e.g. if you’ve used Git before – please help others who are catching up.

4. Very Brief Intro to the Command Line: going behind the scenes (but the usual scenes)

Much as a repository is just another name for a file folder you’re tracking, the command line is just another way of seeing the files you’re used to seeing in windows. (Lowercase ‘w.’)

To get where you’re going:

cd path/to/your/folder # change directory

ls # list directory contents

Download the folder, preserving the connected history:

git clone %clone_url%

Core commands you’ll need often:

git status

git pull # download changes from GitHub

git status # start of loop

git add %filename%

git status

git commit -m "your headline commit message" -m "your optional extra details, if you want them, just go in a second message."

# repeat loop as desired

git push # publish your changes

5. A little command line setup for the Soundscape Narrative

Armed with that primer, let’s do one more thing at the command line before you go out and start recording and editing soundscapes.

HW for next time:

- Download the Audacity audio editor, or update to the latest version if you already have it.

- Optionally also download the separate FFmpeg import/export library

-

Bring headphones – we should have time to practice using it!

- Listen to the following recordings made by students in response to a similar prompt:

- Barner, Tyller. “Coffee Shop Conversations.” Digital Media and Pedagogy Showcase Spring 2019. http://dmap.pitt.edu/node/248.

- Funke, Taylor. “Soundscape - Day In: Day Out.” Digital Media and Pedagogy. http://dmap.pitt.edu/node/177.

- Johnson, Beth. “Hello.” Digital Media and Pedagogy Showcase Spring 2019. http://dmap.pitt.edu/node/249.

- Wick, Thomas. “Soundscape - Expedition to Planets Unknown.” Digital Media and Pedagogy Showcase Spring 2018. http://dmap.pitt.edu/node/178.

- Listen, as well, to the following audio tracks from the first few minutes of successful TV dramas:

- Breaking Bad. Sound extracted from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D-G8weg2Ndg under Fair Use, for instructional purposes.

- Battlestar Galactica. Sound extracted from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9VBTcDF1eVQ under Fair Use, for instructional purposes.

-

Write a short blog post on the issue queue: What do you notice, i.e. what stands out while reading or listening? What does that suggest, or what does it make you wonder?

- Optional: This will be part of the homework for next weekend, but if you want to get a head start, read the following advice on sound recording, listening to the embedded clips:

- Fowkes, Stuart. “The Top 5 Things You Need to Make a Great Field Recording.” Cities & Memory: Field Recordings, Sound Map, Sound Art, 13 Aug. 2014, https://citiesandmemory.com/2014/08/top-5-things-need-make-great-field-recording/.

- MacAdam, Alison. “6 NPR Stories That Breathe Life into Neighborhood Scenes.” NPR Training, 30 Oct. 2015, https://training.npr.org/audio/six-npr-stories-that-breathe-life-into-neighborhood-scenes/. (Note the time skips she recommends: sometimes a long clip is embedded, but not meant to be listened to in full.)