Writer/Designer’s studio: web unit

Work to have done:

- As much of the Interneting is Hard tutorial as you can – at least parts 1-6 (from “Introduction” through “CSS Selectors”), with exercises pushed to your repo’s “tutorials” folder

- More on CSS selectors: the CSS Diner game and/or a CSS-Tricks roundup

Plan for the day:

- Threshold Concepts: what you all need to know

- Ideas for studio

- Set goals and go forth!

- Update your goals

1. Here’s what you need to know today

Start by thinking about structure (i.e. HTML before CSS)

Remember that though you probably have a vision for how your site should look, it makes sense to begin by thinking about the structure of your content. That will give you the material you need to support multiple views, depending on screen size and/or what begins to feel most important.

So I recommend starting by listing and grouping:

- What are the content sections your site will include?

- How might you group those things hierarchically? That is, what’s the most important for a viewer to encounter first? Which things are (or could be) parts of others, and which things have to be at the same level?

- If you can make a nested list of your content areas, that could serve you as a navigation… and probably also a list of headers (

h1,h2, etc).

You don’t have to reinvent the wheel

Like other kinds of media, web design has its genres… and certain genre conventions that solve recurring design problems. You can find some of these by looking at the code of websites you like: you can right-click on any page and choose “View Page Source” (or something like it) to see the full rendered HTML page. From there, you can also click the link in the head to see the full stylesheet.

For instance, a very common structure you should all know about is this one, for a basic navigation menu:

<nav class="main-nav" id="main-nav">

<ul>

<li class="active"><a href="/index.html">Home</a></li>

<li><a href="/about.html">About the Author</a></li>

<li><a href="/articles.html">Past Publications</a></li>

<!-- etc -->

</ul>

</nav>

Note that:

- The semantic element

<nav>automatically communicates the navigation role to audio screen readers, helping blind users find their way around your site. - We use list items so screen readers can easily enumerate the number of locations

- You can use a class like “active” to keep site visitors oriented within the space of your site. (There are other ways, too, but this is pretty simple.)

You can then style that menu to your heart’s content:

/***** Main menu styling *****/

.main-nav {

background-color: #eee; /* light gray */

}

.main-nav a {

color: #4b8568; /* dark green */

}

.main-nav ul {

list-style-type: none; /* Hide the bullets */

display: flex; /* Arrange horizontally, not vertically */

}

.main-nav li {

padding: 1em 2em; /* Add a little space around each link */

}

.main-nav .active {

background-color: #4b8568; /* dark green, same as link color */

}

.main-nav .active a {

color: #eee; /* light gray, same as navbar */

}

/* etc */

Note that:

- We don’t need a specialized “button” element for navigation: we’re not submitting anything, we’re following hyperlinks.

- Instead, we can just style our

<a>or<li>directly (or by adding classes directly to those elements), so it looks and feels like a button. - This is a direct outcome of the Box Model you read about in the tutorial.

When you’re ready to work on appearances, test CSS rules directly in the browser

As some of you have discovered, the HTML previews you can get within VS Code are only really approximations of what you’d get in a real browser. So you probably want to get in the habit of having your file truly open in Firefox or Chrome.

Why those two browsers? Because they have great built-in developer tools to “inspect” elements of the page. It’s already available: just right-click anywhere and choose “inspect element” to see the local html, the full cascade of CSS rules that apply to it, and a few other features beside.

This is helpful for a number of reasons:

- First, to see how an existing site works. Viewing the full page source is great for seeing how professional designers organize their documents, but most of the time, you'll want to be more targeted: you don't _want_ to have to sift through everything just to figure out the color or font on that one blockquote or button (or whatever it is you want to imitate and thereby learn from). The inspector lets you zoom in on one html element, and leave everything else collapsed (until you want it).

- Second, any time you can't figure out why something's not working, the inspector is your best friend: it shows what the browser thinks you told it to do, rather than what you hoped you told it to do.

- Third, you can use the inspector to simulate a mobile device! Look for the phone symbol.

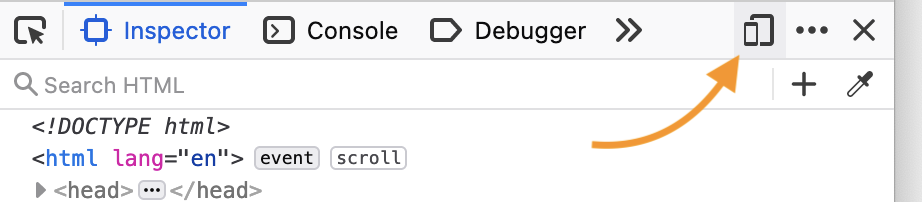

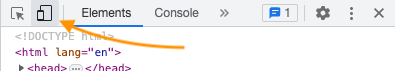

In Firefox, the button's on the right of the toolbar In Chrome, it's on the left

- Crucially, you can also add CSS rules and immediately see what effect they would have on the page. (Safari users, note that the button to add a new rule is on the bottom left, not the top right as in the other two browsers.) Color pickers are an especially nice feature – and perhaps the one thing that Chrome's inspector does better than Firefox's at the moment, in that Chrome lets you change from hex color to RGBA or HSL, and directly adjust saturation / luminosity, e.g. to improve contrast.

Just be sure to copy your changes to a file for safe keeping, or they'll disappear when you refresh!

To make copy/paste easier, click on the source your browser created for your new rules: in Firefox it's called "inline", in Chrome "inspector-stylesheet", in Safari "Inspector Stylesheet."

2. Ideas for studio

In a moment, I’m going to invite you to set goals for studio time: if you’ve kept up to date with the tutorials, you should now know enough to really start coding your own content!

If you haven’t yet sorted out your navigation, that’s a great place to start.

Here are some other things to consider as you move forward:

The semantic html tutorial would be useful now, as well as later!

I hadn't initially scheduled it at this point in the tutorial, in large part because the tutorial itself doesn't introduce semantic elements like <section> and <nav> until later. But you may well find them easier to use than <div>, <div>, <div> all the time!

It'll also set you up well for the accessible HTML workshop tomorrow!

Your homepage should probably be called something like index.html

I'm going to recommend that everyone use GitHub Pages to publish your sites unless you have a good reason not to. (And you might; but talk to me about it.) In that system, you store your files in a GitHub repository (in a branch called "gh-pages," like this site, or a subdirectory called "docs" – look in your own repos!), and GH knows where to look to find your stuff. By default, it'll show your README.md file as the home page, unless it finds a file called index.html or index.md.

Therefore, rather than call your landing page myproject.html, landing.html, or home.html, you're better off using the index.html name. You can always change the <title> to give it a more accurate name in the browser tab. : )

Strive for semanticity.

Ask yourself:

- Can you tell what's going on just by reading the HTML file?

- Do your header levels (

<h1>, <h2>, etc) correspond to your intended hierarchy? Don't skip levels. - Does the HTML hard-code any display (e.g.

<center>,<b>) that should be in the CSS? (Older tutorials will suggest this, but it's not a great idea.)

Let appearances reflect the structure, not vice-versa

This one's related to what I said above, but applies especially when you're starting to think about appearances. Visuals are volatile; structure should be steady. It can be very tempting to just accept your browser's default styles as a given, e.g. to jump from a large <h1> page title to an <h5> subtitle because the latter "looks about right." But this would mis-represent the actual structure of the document – and would seriously confuse screen-reader software trying to present the page to a blind visitor. Instead, use your browser's Inspector to take note of the CSS rules defining that <h5>, and apply them to <h2> in your stylesheet.

Stuck for what to do, CSS-wise? Start with some basic spacing

Work your way through Web Design in 4 Minutes, and borrow some of the most essential rules... e.g.

- set a maximum width for text

- add padding on main content and headers

- change font-family away from the default "Times"

For more advanced layout (sidebars, columns, grids, etc), see the links in the homework assignment.

3. Go forth!

In the shared google doc, set a goal for today: what do you need to do to level up on HTML, CSS, and resource gathering to move toward your specific project? Note that a Website Preview is due a week from today.

Save about five minutes at the end to write me a brief exit note about what you’ve been working on.

4. Exit note

Homework for next time

- View Kevin Powell’s video on 5 simple tips to making responsive layouts the easy way. It’s also just a really useful channel to know about!

- Do more of the tutorial, including at least Flexbox (8) and Responsive Design (10), if you haven’t yet.

- As a reminder, you should write out the exercises in the tutorials and push them to your repository – probably in the tutorials subfolder. Once you have them working as presented, feel free to update them to test out ideas for your own site! But do try to confirm you can get them working first. HTML, like all code, is fiddly: punctuation (including spaces) matters for things like close-tags and CSS selectors.

- Separately, also read about Grid Layout (and optionally the followup post on responsive grid).

- EXT: Want more CSS Grid templates and examples, including CodePens to play with? Try [Grid By Example](https://gridbyexample.com/patterns/, which also has video tutorials.

- Compose and push a first website preview: a beginning, focused on content and navigation.