Lesson 5: Sources, Citation, Studio

Texts to have read / listened to / watched

- "Working with Multimodal Assets and Sources," by Ball, Sheppard, and Arola

- "Breathe Life into Neighborhood Scenes" by Alison MacAdam, from NPR Training

- Tips for Recording Audio on a Phone, a LibGuide from the University of Dayton

Work to have achieved

- An audio narrative proposal, posted to the issue queue (and optionally to your own repository)

Plan for the day

- Sourcing ethics and GitHub: ignoring files and folders (5-10 min)

- Sourcing ethics: key concepts and practical takeaways (~10-20 min)

- In-class studio (~45 min)

- Read composing advice

- Set explicit goals

- Work on your own (ask for help/advice as needed)

- Exit note

- Sharing fun clips (from last time? from today?)

- Homework: audio narrative preview

1. Sourcing ethics and GitHub: ignoring files and folders

As you know from Writer/Designer, there are some source files that we have implicit license to reuse and distribute (e.g. public domain), some that we have explicit license to reuse and distribute, albeit potentially with some restrictions (e.g. Creative Commons), and some that we can make limited fair uses of, but can’t distribute in their entirety (copyright).

But if we’re working with a public repository on GitHub, what are we to do with source files we aren’t allowed to distribute?

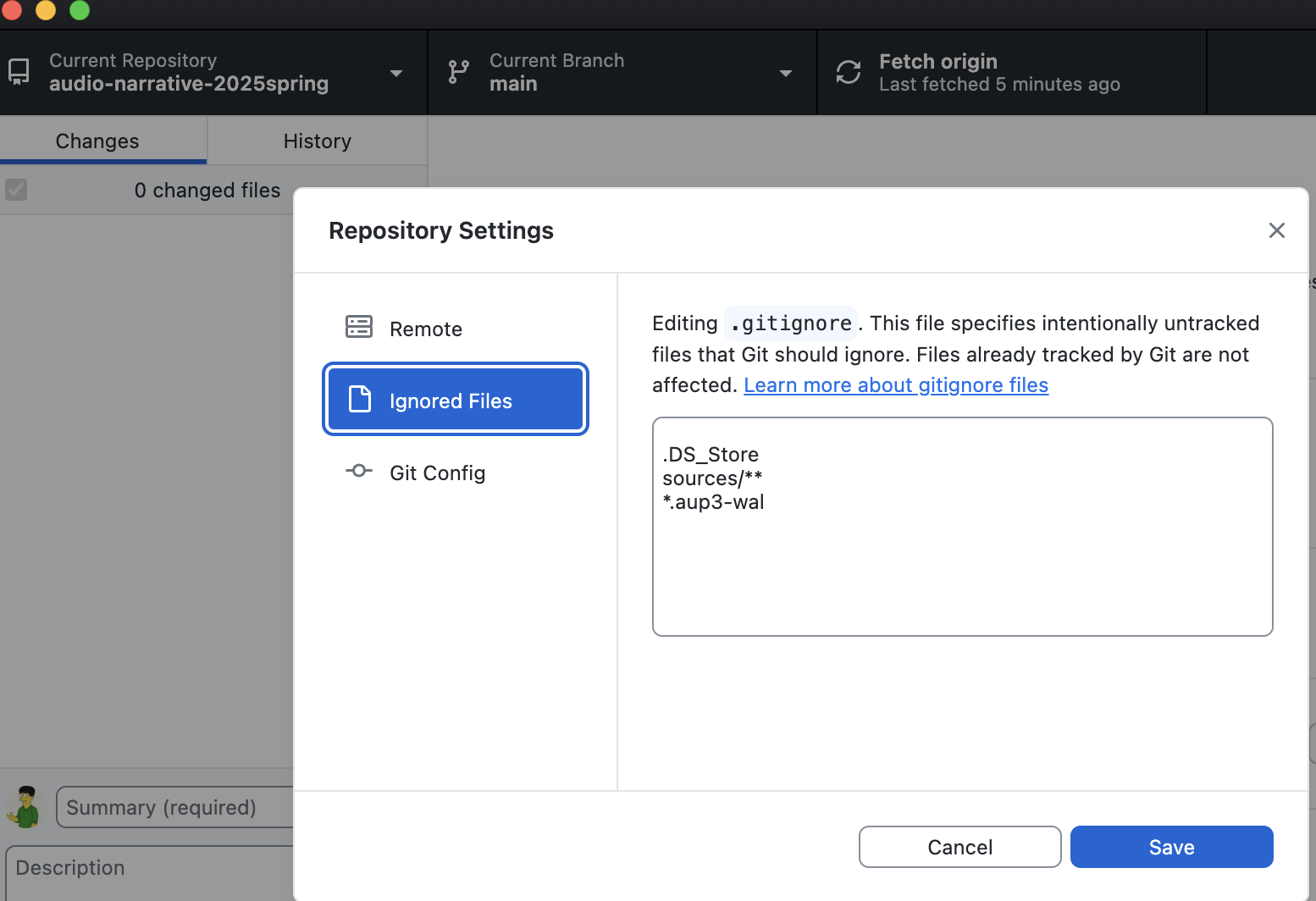

GitHub offers a solution: the .gitignore file. Any file path that matches the patterns in that file won’t be tracked or version controlled. In the assignment repository you cloned from me, I had already pre-populated that file with the line sources/**: in other words, any file in the “sources” folder should be ignored.

You should see that the file was deleted from its original location… but not added to its new location, because GitHub can’t see inside the sources folder: it’s been ignored.

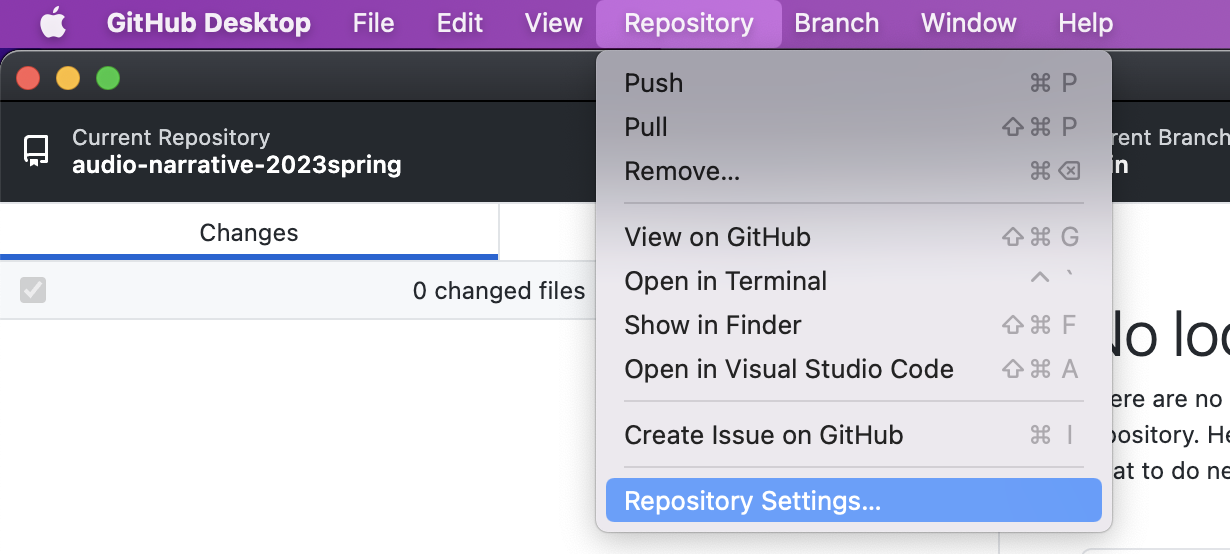

Should you ever want to change what git/GitHub is ignoring, you can! In GitHub Desktop, go to the Repository menu, then select Repository Settings > Ignored Files… or just edit the .gitignore file in your text editor of choice.

Show me

2. Sourcing ethics: key concepts and practical takeaways (10-20 min)

I’m going to ask you to group up again and work through some questions about the reading/listening from the last week, which I’ve set up as a quiz in Canvas. Don’t worry, it’s not factored into your grade! But I do still want to make sure you understand these things.

Discuss before putting in your group's answer, and then please pay attention to the notes that I've added to my answers. We can talk through any questions or discrepancies; call me over!

When you're done discussing these questions (and answers), head back here for some more open-ended prompts to discuss within your group.

Some questions you should be able to zip through quickly; others may require more discussion. Heads up: even several of the True/False questions are more complicated than that binary implies! ;)

Quiz questions, for future reference

- True or false: if you can find it on the internet, you can use it in your project.

- True or false: the only sources you can use in this project are those you record yourself.

- True or false: if you record your own sources, you don't have to cite them.

- True or false: if you use a source with a Creative Commons license, you don't have to cite it.

- True or false: to cite a source with a Creative Commons license, you should be sure to write "licensed under the Creative Commons."

- True or false: you're not allowed to mix assets from CC-BY and CC-BY-SA licensed sources.

- What's the difference between fair use and Creative Commons?

Discussion questions

When you’re done with the quiz, and you’ve gone over the notes, talk through these. Take notes in our shared google doc: bit.ly/cdm2025spring-notes.

- How would you define a “credible citation” in relation to the audio narratives you’ve proposed?

- Why do you think Ball, Sheppard, and Arola are so insistent about folder structure and file naming conventions?

- Would you (each of you, specifically, for this project) want to work from a written script? Why or why not?

- Would you (again, each of you in your group, today) want to incorporate human voices in your audio narratives? How or how much, and why (or why not)?

EXT: Bonus questions for the swift

- Does my use of the “Piled Higher and Deeper” comic in lesson 2 fulfill the criteria of fair use? Consider all four major factors.

- What’s one way to make sure you’re recording the sound you want to (and not, say, the loud bus passing by your conversation)?

- What does MacAdam consider tempting cliches of soundwriting, and how does she suggest getting past them?

- EXT on the EXT: Read through the link at the top of Fowkes’ piece: Top 10 Simple Field Recording Tips. Any surprises that others in the class should know about? Let us know in the notes doc!

Homework preview (5 min)

3. In-class studio

Most of the rest of the day will be time to work on your own: scripting, finding sources (and recording TASL information: Title, Author, Source, License), importing sources into Audacity to extract assets, arranging assets into a story, etc.

But first, read through my notes below, and then write a short note about your goals for the day in the shared notes doc: what are you working on today?

When it’s time to stop (around 2:00 or 2:05), I’ll ask you to return to this note and reply to yourself: how’d it go? What’s your new goal for the next time you work on this project?

3a. Composing advice, mostly based on proposals

Lots of great ideas in those proposals. My small bits of broadly applicable advice as you get underway:

Record some "silence" every time you record

As we discussed last time, every location has its own characteristic background noise. If you're recording in more than one place (or sometimes, the same place at different times), you might be able to hear the difference, especially if you're not recording under ideal conditions, e.g. with sound absorption on your microphone etc. BUT if you record a few seconds of that background before or after what you're hoping to use in your project, you'll give Audacity what it needs to try to Noise Reduction.This is my life (not someone else's)

If you're doing a day-in-the-life, a commute, a night out, the challenge is to make at least some of your narrative different from everyone else's: parts of a particular soundscape, not a generic one. Voiceover, even the little mutterings of a solitary person to themselves, may help; your choice of a soundtrack overlay might, as well. Or, like Will or Weini, you might decide that this particular day is less typical than it seems at first...Consider getting it in writing

One benefit to drafting a project in prose is that your script doubles as a transcript – which improves both accessibility and discoverability. It also means you get clean version history as you revise your script. (One downside is that it's sometimes easier to do or say than it is to write.) Still: something to keep in the back of your mind, especially if you're working on something fictional or working with voice actors.Roll tape!

On the flip side, if you're proposing something where you're not sure what you'll find, consider a journalistic approach: record more than you think you'll need; narrate what you're doing as you're doing it; then add a post-hoc voiceover that makes sense of (tells the story of) what you ultimately found.Need to show time passing? Try a cut – or a crossfade

If your proposal covers a long time – a full day, a full game, etc – you won't be able to represent it minute by minute. Instead, you might want to jump from moment to moment with a sharp cut from one background track to another. (Compare this to panels in comics, or cuts between camera shots in film.) But if you want to give a sense of time passing without changing where you are, one option is to fade out from the first moment while you fade in the later one. You can even do this with parts of the same musical track. You should get a sense of change within sameness – a kind of auditory montage.3b. Set a goal

3c. Go for it! (40-45 min)

Do whatever work you need to get something toward your project posted to your GitHub repository by the night before our next class: find audio sources you have permission to use, extract assets from them, record test voiceover with your phone or computer, start moving things around in Audacity, practice some more with GitHub Desktop (or command line git).

Save as you go, and commit when you have something to say about what you’ve achieved. Remember: thanks to version control, you won’t need to rename this file, so call it something that will last.

The goal for now is to get a feel for how you work with audio, not to have a finished product. In our next class, we’ll use your experience to refine our shared baseline criteria and brainstorm some aspirational goals.

Call me over if you need help with Audacity, Git/GitHub, or determining the license on an audio source!

Homework for next time:

- Look over the audio resources on the site, and dig into anything that seems like it would help you.

- Work on your audio narratives, getting at least two sound assets in Audacity in conversation with each other. If you have time, do more!

- Push a preview of your project to your GitHub repository. As per the assignment prompt, this should include:

- A layered Audacity project file (.aup3), showing the arrangement of your sounds so far, however rough. (It need not be a complete soundscape or narrative yet.) Remember: thanks to version control, you won't need to rename this file, so call it something that will last.

- At least one static screenshot (.png or .jpg) of your Audacity file in progress. (You'll use this in your final reflection, for comparison later to subsequent drafts). Note that link: you shouldn't use your camera for this!

- A plain text (.txt) or markdown (.md) file, explaining in at least 300 words what you're showing us in this preview. Feel free also to ask questions or lay out next steps for yourself!

- An updated list of assets (either directly in README.md or in a separate assets.md / credits.md file), indicating which the files you've actually recorded or otherwise obtained. Add source documentation for any outside sources – along with your permission to use them (e.g. licenses, fair use; see Writer/Designer p. 160-165).

- Finally, export a playable mp3 file, both as a snapshot and just in case something goes awry with your Audacity project file.